Christopher Wilkins was going to be president. At least, that’s what his parents said. He went to George Washington University for political science. He scored himself internships in Congress and the White House. In every perceivable way, Wilkins was all geared up to be a politician.

The only problem with the plan was that he absolutely hated everything about it.

“I hated just about everything with political science, and I hated just about everything with economics as well,” he said. “I had literally the best school in the entire United States for political science, and a life of politics afterward. I had all the opportunities there, and I just hated it.”

One of Wilkins’ first experiences when he got into the university took place in a large lecture hall, which was a jarring difference from his small high school in Orange County, California. The lecturer was a prominent economist. So prominent that he’d regularly give speeches to Congress about the economic viability of different bills.

“He was a very well-known character,” Wilkins said. “That said, he was a terrible educator. In fact, everything that I strive to do as a teacher is the antithesis of everything he was as a teacher.”

A significant problem in colleges is that people are not hired to be teachers, they’re hired to be researchers. And that professor was a brilliant researcher. But if any student asked a question, they’d be ridiculed. He meant it as a kind of joke, Wilkins thinks, but it created a very hostile environment.

The whole purpose of learning is to be intellectually curious. That’s what Wilkins loves about his students—their intellectual curiosity. His goal is to foster that curiosity.

“If someone asked me a question, I would sooner be caught dead than get mad at them for asking that question,” he said.

He eventually stopped showing up to those lectures. He didn’t feel engaged in the class, which is saying something, because he always thinks he has something to gain from being in a lecture hall. He always has something to learn. But he soon realized that there was no point in attending an expensive school studying something other than what he loved.

While he studied political science, Wilkins took a class on Byzantine forms in architecture and thought it was the coolest thing. He loved it, and he wanted to do more related to Byzantine art in architecture.

He then took a class on medieval philosophy. He thought, “These stories are awesome!”

Those were the two classes that he absolutely loved. If he could get in a time machine just to go back and take those classes again, he would. It just so happened that those classes were focused on Greek and Latin.

“I was always going to end up here,” he said. “By fate, it happened that I ended up doing it.”

His fascination with the Greeks and Romans sparked when he was a kid.

“When there were construction projects on our neighborhood, we would have the builders who would cast off their concrete and wood, and my friend and I would kind of pilfer through that rubble. And we would repurpose it in creation of various things to make small civilizations. He was very inspired by the Norse. So he created Viking settlements out of the wood and I took those cement pieces and created little Roman environments. So, I’d always been inspired by the Greeks and the Romans.”

Wilkins bounced around for a while after leaving George Washington University. He attended a community college and then decided to transfer to the University of California, Davis. He wanted to study computer science, but he didn’t have enough math credits to transfer into the program. So, he chose to apply to the classics program instead.

“In my mind, I thought, ‘Well, this is something that I’ve been interested in, so I could write about why I wanted to do this on my college admissions, and I’ve also taken all of the requirements, which means I would just be offered admission,’” Wilkins said. “Once I got my foot in the school, I would then change majors to computer science. That was the plan right from the get-go.”

Once he showed up at UC Davis and met his teachers, his plan changed.

“I had the most wonderful, supportive teachers who cared about me as an individual, who cared about my well-being,” he said. “One of the joys of classics is that it is small. Not many people do Greek or Latin. So, we are a tight-knit community. All of my friends in classics became some of my best friends ever. I still talk to them to this day.”

Wilkins also uses the skills he learned in those classes to this day.

“Very recently, in fact, when I say recently, I mean literally yesterday, I was reading medieval spooky horror stories,” he said. “And I can now finally read the words of Saint Francis of Assisi in Latin and Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of Britain, which is kind of a snooze.”

In 2017, Wilkins started his new journey at the University of Kansas. In 2019, he received his master’s degree in classics. Since then, he’s been teaching Latin at Shawnee Mission South.

“A lot of people go to school, and after graduation, they don’t do something that’s related to what their major is, which is fine,” he said. “But for me, I always wanted to do something related to Latin or Greek. And teaching was kind of the natural conclusion of that.”

The only question was who he would teach. Elementary students? Middle school students? College students?

“That’s where I was unsure,” he said. “But then after I graduated from KU, I found the job here at South and was hired very quickly to the position, then the rest is history from there.”

His initial concerns were with preparing to be the best teacher he could.

“I’d love to say it just came naturally, but the answer is, it was hard,” Wilkins said. “And, sometimes, it can still be somewhat hard. Like, should you do this activity or this activity? It’s much easier with time, but it’s always a little bit of a difficulty at first.”

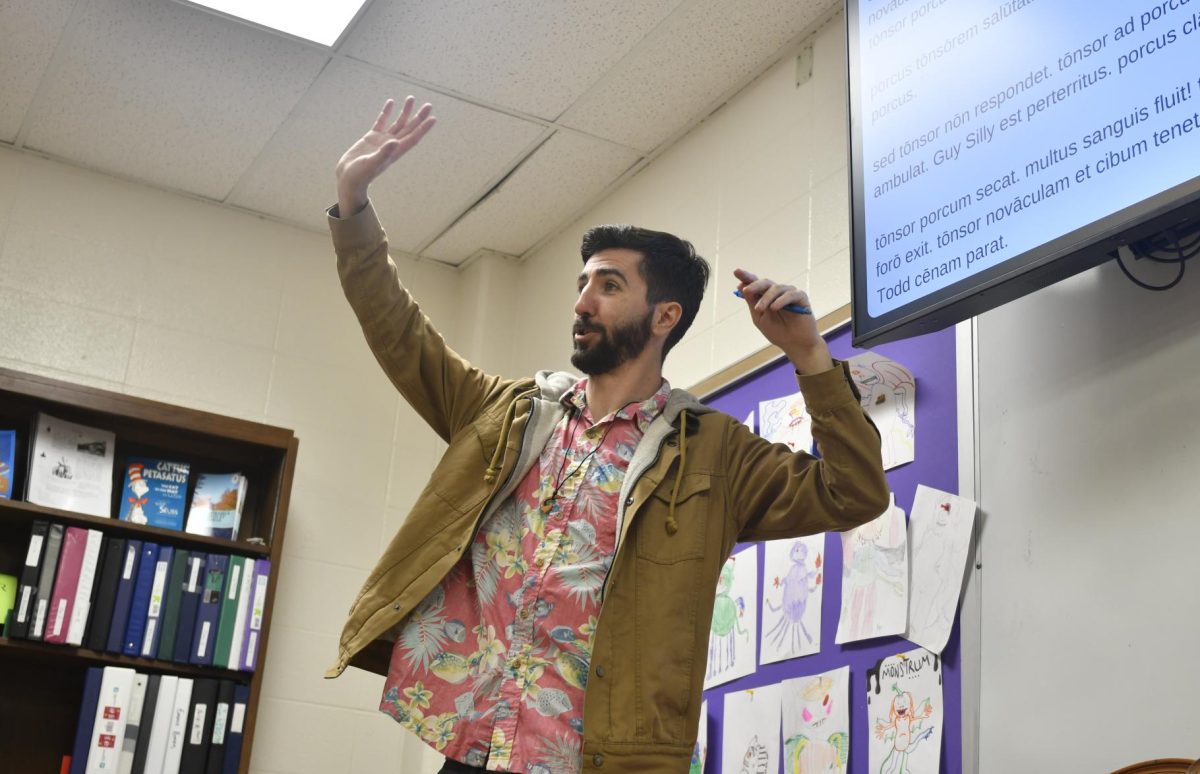

Over his time as a teacher, Wilkins has found his own unique, hands-on way of teaching. His favorite lesson includes students learning about monsters from ancient mythology, and then creating their own using vocabulary words they learn in class.

“I try to be as active as possible,” he said. “I love having my students not just read through something, but adapt it and use it for their own purposes. I love having students take pictures of things or draw them or make me sentences based off of new vocab words to cement that vocab in their mind, but also just help them apply the word to other knowledge that they knew beforehand.”

He sees the benefits of handing out worksheets but prefers not to.

“I want students to kind of live vicariously through the language to see that this is not just something for ancient people, but for modern people as well.”

Nothing brings him greater joy than seeing students really get into the material.

“I could tell my students, ‘Here’s what I want you to know. Here’s what going to be on the quiz,’” he said. “They could all ace the quiz. And they’ve learned the things that I taught them. Great. But it goes beyond. It’s about the curiosity—the spark to know more or just the love and the passion of the things that they’re doing. With all of those constraints in mind, if they’re met, I’m a very, very happy teacher.”

Wilkins knows that Latin is “weird”—as some of his students have described it. He’s seen the memes about vocabulary lessons in Latin class versus any other language class. He chooses to embrace the weirdness of it all. Wilkins thinks some people might take offense to it, but he loves it when he himself is described as weird.

“Profe [Patrick] Grant once said something about me,” Wilkins said as he sat in a red chair he refers to as his throne. “He said, ‘You are the most extra person I’ve ever met.’ I wear that like a badge of pride because Profe Grant can be very extra with his students. I love that about him. I love the things that he’ll say in Spanish or English. Cracks me up. So, for him to think I am extra, that is truly a great thing in my mind.”